Sure, they’re both four-syllable words starting with M*, but do they have anything else in common?

Actually, quite a lot. They’re both ancient mental technologies for refining the mind’s ability to focus and grasp what is fundamentally ineffable: for mathematics this is space, motion, and quantity (or number); for meditation (I’m thinking here of Buddhist jhana meditation) it is the nature of mind and thought itself. Both require many years of intensive training and apprenticeship, often focusing on learning to solve a set of standard problems and carry out fixed exercises and incantations (QED, induction on n, proof by contradiction; buddham saranam gacchami). The practitioners of both are generally viewed as weird and otherworldly, and advanced practitioners demonstrate their mastery with bizarrely abstruse feats such as proving that all integers can be represented as a sum of a finite number of primes, or spending long periods of time in trance states, or levitating.

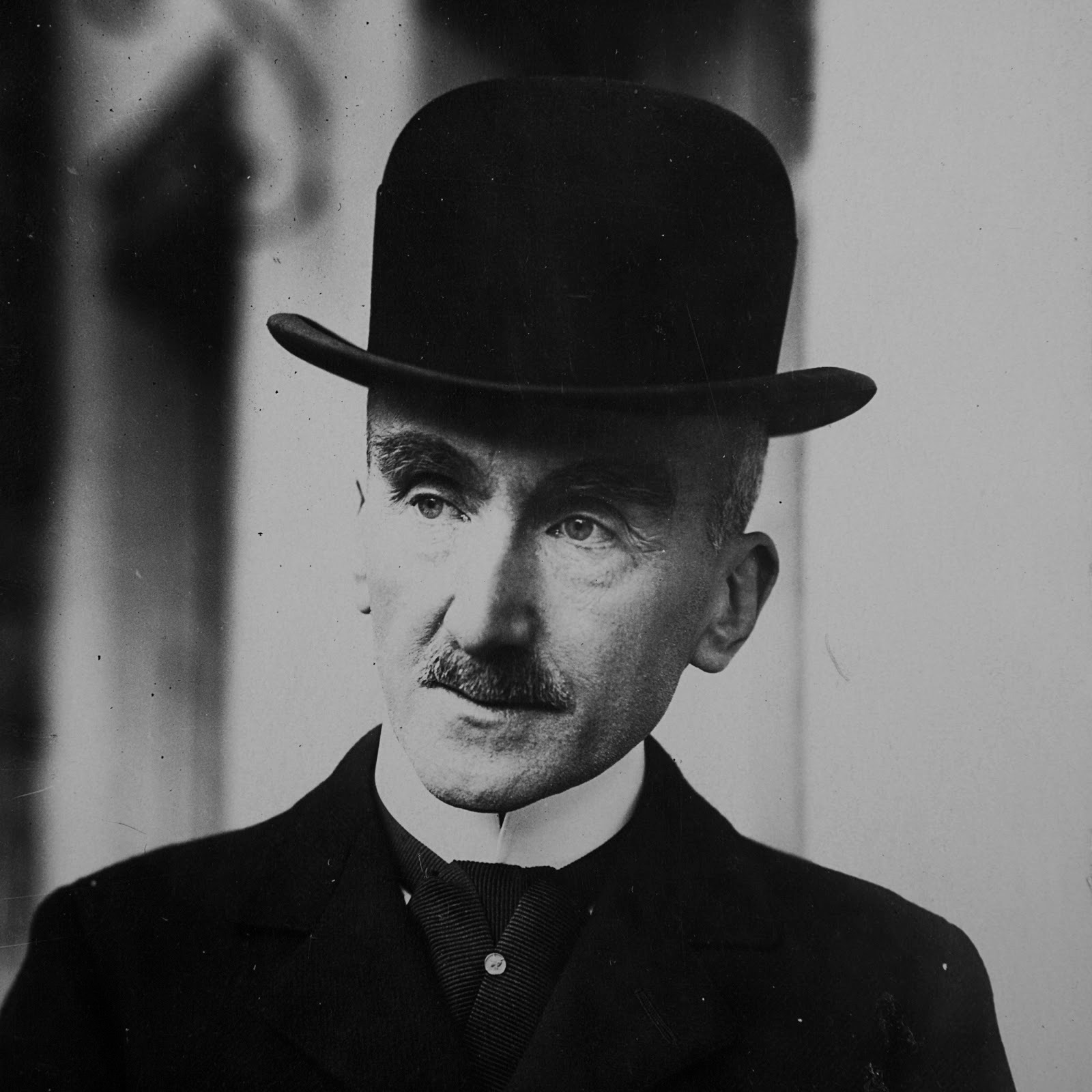

There is some direct overlap as well. Meditative practices often draw on geometric motifs — as in the mandala above — and arithmetic relations. Many chants are built on combinatorial principles. More specifically, the last of the five jhana factors is ekagatta, often translated as ‘one-pointedness’. This is typically interpretted as identification of mind and object, but the Pali word is purely geometric: eka (one) agga (point) ta (state). Viewed from a mathematical perspective you can see that the focusing of consciousness to a point can happen continuously, through contraction, or discretely, through reduction of dimension. It is possible to experience the mind as a geometric space, whose dimension can be reduced through concentration.

Presumably it’s just a coincidence, but I find it fascinating that the modern systematic approach to numbers is often attributed to the work of Euclid, in the early 3rd century BCE, shortly after Indian influences started to filter into Greek philosophy, particularly through the thought of skeptics such as Pyrrho of Ellis.

* Reminding me obliquely of the report I heard on the radio in Germany about 20 years ago about the efforts in Germany to establish mediation as an alternative path for dispute resolution. The expert bemoaned the lack of understanding that the general public had of mediation, claiming that many people thought it was some sort of esoteric process, because they confused the word with meditation. (The German words are the same as the corresponding English words.) That is, at least, a problem I’ve never had with the word mathematics.