I read a novel that I’d known about for a long time, but had never gotten around to: Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven. I was startled to discover that an essentially background point of the plot of this novel, published in 1971, was the destruction of the Earth’s environment by the greenhouse effect. This has already taken place before the events of the novel, set in the early twenty-first century.

Rain was an old Portland tradition, but the warmth — 70ºF on the second of March — was modern, a result of air pollution. Urban and industrial effluvia had not been controlled soon enough to reverse the cumulative trends already at work in the mid-twentieth century; it would take several centuries for the CO2 to clear out of the air, if it ever did. New York was going to be one of the larger casualties of the Greenhouse Effect, as the polar ice kept melting and the sea kept rising.

This is only incidental to the themes of the novel, which grapples with the structure of reality and the nature of dreams. But it amazed me to see global warming being confidently projected into our future, at a time when — as the climate-change skeptics never tire of pointing out — discussions of climate change tended to refer to the danger of a new Ice Age.

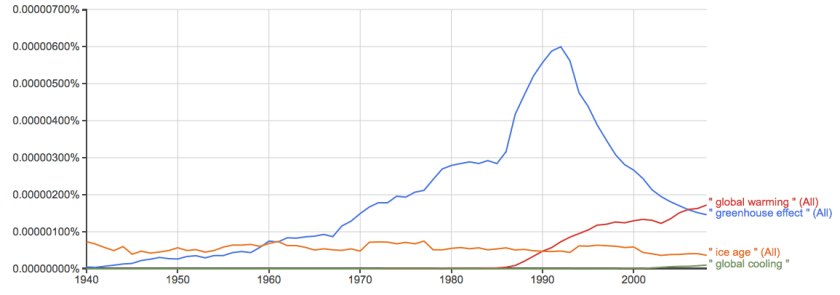

At least, that is my memory. According to the Google Books NGram viewer, though, the “greenhouse effect” was as mentioned in books around 1970 as frequently as it is today; and, oddly, it has declined substantially from a peak three times as high in the early 1990s.

For example, a 1966 book titled Living on Less begins its section on “The Environment” by discussing global warming, and launches right into a description of the greenhouse effect that sounds very similar to what you might read today.