I’m glad he takes the English pronunciation of Farage rather than the rather poncey foreign-sounding one that he seems to prefer.

Category: History

A quiet man

I was just reading this interview with former US Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, about Donald Trump. You could see the cutting edge of Trump apologetics, on the way to determining that the Republican establishment has always been allied with Trump. The trick is to reinterpret Trump’s crude thinking as simply crude (or bold, down-to-earth) formulation of very clever, even sophisticated thinking. And then there’s this:

Isaac Chotiner: You were at a meeting on Monday with other Washington figures and Trump. What did you make of him?

Newt Gingrich: Well, Callista and I were both very impressed. In that kind of a setting he talks in a relatively low tone. He is very much somebody who has been good at business. And he listens well. He outlined the campaign as he saw it. I think he did a good job listening. He occasionally asked clarifying questions. He was very open to critical advice. I am not going to get into details, but I will say my overall impression was that in that setting he was totally under control…

Does none of Trump’s rhetoric about Mexicans or Muslims worry you or upset you?

I think he was too strong in talking about illegal immigrants in general, although if you look at the number of people who have been killed by people who aren’t supposed to be here, there is a fair argument on the other side too.

It makes him seem like a reasonable guy who occasionally gets carried away when speaking with the common folk.

Hitler comparisons are almost never useful, whether for insight or political rhetoric. Trump is not Hitler. Even among 1930s fascist dictators, Hitler is not the one Trump most resembles. Nonetheless, I couldn’t help but be reminded of something Albert Speer wrote, explaining why as a young academic he found himself drawn to Hitler:

What was decisive for me was a speech Hitler made to students, and which my students finally persuaded me to attend. From what I had read in the opposition press, I expected to find a screaming, gesticulating fanatic in uniform, instead of which we were confronted with a quiet man in a dark suit who addressed us in the measured tones of an academic. I’m determined one day to look up newspapers of that time to see just what it was he said that so impressed me. But I don’t think he attacked the Jews….

The Rhodes goes ever on and on

It is decided: The Rhodes statue remains at Oriel College. What was promised to be a long and thoughtful reconsideration of the appropriateness of honouring a notorious racist in the facade of an educational institution of the twenty-first century was short-circuited by threats to withdraw £100 million pounds in donations. The ruling class has spoken! Surely, at the least, we can agree that this demolishes the notion that Rhodes is a mere quaint historical figure, whose ideology is of no concern. Clearly there are quite a few mighty pillars of the establishment who feel that an assault on the honour due to a man who brought great wealth and power to Britain through dispossessing, subjugating, and frankly murdering members of what he considered “childish” and “subject races”.

Most bizarre is the appearance of an extreme form of the standard political-correctness jiu-jitsu, whereby students raising their voices in protest constitute an assault upon free speech, while the superannuated poobahs who tell them to shut up until they have their own directorship of a major bank are the guardians of liberty. And we academic hired hands are neglecting our pedagogical duty if we don’t help them tie on the gag.

As I remarked before, they talk as though the protesters sought to excise the name of Rhodes from the history books with knives and acid, rather than proposing that the Rhodes statue be removed from its place of honour to a museum, where it can be viewed neutrally among other historical artefacts.

There is an argument that says, the Rhodes Must Fall argument points to general iconoclasm. What statue would stand if we judge the attitudes of our past heroes by contemporary standards. Putting aside the question of whether a complete lack of granite equestrians would impoverish modern urban life or undermine public morals, there is a vast difference between a historical figure who is honoured for great accomplishments and services to his country, but who shared in what we now consider benighted attitudes of his time; and Rhodes, whose accomplishments consist in dispossession and subjugation of other races. Take away the racism and imperialism from Rhodes and nothing remains.

Obviously, different views of the Rhodes statue are possible. What I find extraordinary is the accusation that even to raise the issue is somehow improper. That this is presented as a defence of free speech only demonstrates how the implicit critique has driven some portion of the elite into unreasoning frenzy.

When did it become verboten to rewrite history?

The role of chancellor is a difficult one: He’s the symbolic aristocratic authority figure, of modest intelligence but sterling character, set to superintend the carryings-on of the overly clever boffins.

Anyway, there’s been a bit of to and fro at Oxford over the position of Cecil Rhodes. Following the successful “Rhodes Must Fall” protests at the University of Cape Town, Oxford students have been demanding that Oriel College remove the statue of Rhodes prominently displayed in the college’s facade. Oxford’s chancellor, the failed Conservative politician and last colonial governor of Hong Kong Christopher Patten, has decided to stoke the flames by using his ceremonial platform, where he was supposed to be welcoming the university’s first woman vice chancellor, to attack those who wish to “rewrite history”:

We have to listen to those who presume that they can rewrite history within the confines of their own notion of what is politically, culturally and morally correct. We do have to listen, yes – but speaking for myself, I believe it would be intellectually pusillanimous to listen for too long without saying what we think…

Yes. “We” must say what “we” think. Since history has been written once and for all, correctly, it is inappropriate to rewrite it. And heaven forfend that the rewriters should rely on their own notion of what is correct, morally or otherwise! It’s about time we got rid of all those people who try to rewrite history, you know, what are they called? Historians.

It’s pretty bizarre. It’s not as though protestors are breaking into the Bodleian and excising the name of Rhodes with a razor blade. The existence of the Rhodes statue is clear testimony to his outsized influence and to the honour accorded to him in his day, and it would continue to serve this function if it were placed in a museum. To continue to display the statue on the façade of a college is a declaration of current respect for him. Which is a matter of public debate. In 1945 all the Adolf-Hitler-Strassen in Germany were renamed, and I don’t recall whether Patten protested the felling of the Lenin statues in Berlin in 1989, or the Saddam Hussein statues in Iraq.

(A friend of a friend of mine, when I was an undergraduate at Yale, made the unfortunate choice to issue the bootlicking pledge in her application essay for the Rhodes scholarship, that she would aspire to fulfil the spirit of Cecil Rhodes. At interview she was asked, “Were you thinking of Rhodes’s spirit as a racist, as a colonialist, or as a paedophile?” Her answer was not transmitted, but she was not awarded a scholarship.)

(Personally, I would have attended the ceremony, to have been present at the historic investiture of Oxford’s first woman vice chancellor, if only I’d been able to rewrite the historical dress code, since at the last moment I couldn’t locate the academic hood required for attendance.)

Early greenhouse

I read a novel that I’d known about for a long time, but had never gotten around to: Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven. I was startled to discover that an essentially background point of the plot of this novel, published in 1971, was the destruction of the Earth’s environment by the greenhouse effect. This has already taken place before the events of the novel, set in the early twenty-first century.

Rain was an old Portland tradition, but the warmth — 70ºF on the second of March — was modern, a result of air pollution. Urban and industrial effluvia had not been controlled soon enough to reverse the cumulative trends already at work in the mid-twentieth century; it would take several centuries for the CO2 to clear out of the air, if it ever did. New York was going to be one of the larger casualties of the Greenhouse Effect, as the polar ice kept melting and the sea kept rising.

This is only incidental to the themes of the novel, which grapples with the structure of reality and the nature of dreams. But it amazed me to see global warming being confidently projected into our future, at a time when — as the climate-change skeptics never tire of pointing out — discussions of climate change tended to refer to the danger of a new Ice Age.

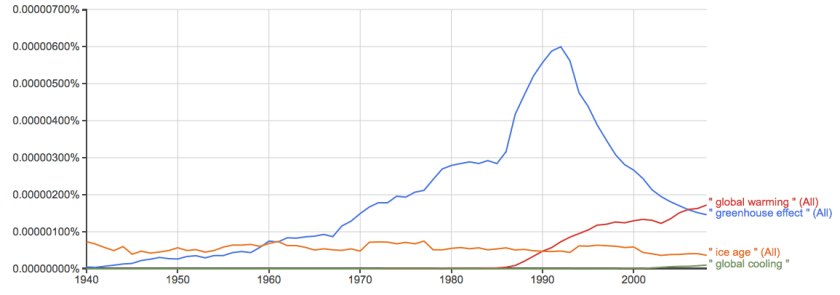

At least, that is my memory. According to the Google Books NGram viewer, though, the “greenhouse effect” was as mentioned in books around 1970 as frequently as it is today; and, oddly, it has declined substantially from a peak three times as high in the early 1990s.

For example, a 1966 book titled Living on Less begins its section on “The Environment” by discussing global warming, and launches right into a description of the greenhouse effect that sounds very similar to what you might read today.

Condorcet method for choosing a religion

Making choices is hard! Particularly when there are multiple possibilities, differing in multiple dimensions. Like choosing the best religion.

There are many possible methods, leading to a variety of outcomes. The 18th century French mathematician Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas Caritat, the Marquis de Condorcet, advocated privileging methods of deciding elections that will always grant victory to a candidate who would win one-on-one against each other candidate individually. (Of course, there need not be such a candidate.) Such methods are referred to as “Condorcet methods”.

I’ve just been reading The Jews of Khazaria, about the seventh to tenth-century kingdom in central Asia that converted to Judaism around the middle of the ninth century.

According to the Reply of King Joseph to Hasdai ibn Shaprut, one of the few surviving contemporaneous texts to describe the internal workings of the Khazar kingdom,

Each of the three theological leaders tried to explain the benefits of his own system of belief to King Bulan. There were significant disagreements between the debaters, so Bulan went a step farther by asking the Christian and Muslim representatives which of the other two religions they believed to be superior. The Christian priest preferred Judaism over Islam, and likewise the Muslim mullah preferred Judaism over Christianity. Bulan therefore saw that Judaism was the root of the other two major monotheistic religions and adopted it for himself and his people.

How to rid the world of genocide

One of my favourite Monty Python sketches is “How to do it“. It parodies a children’s show, teaching children how to do interesting and cool new things — in this case, “How to be a gynecologist… how to construct a box-girder bridge, … how to irrigate the Sahara Desert and make vast new areas of land cultivatable, and… how to rid the world of all known diseases.” The method described for the last is

First of all, become a doctor, and discover a marvelous cure for something. And then, when the medical profession starts to take notice of you, you can jolly well tell them what to do and make sure they get everything right, so there will never be any diseases ever again.

I think of this sketch often, when I hear a certain kind of blustering politician, most commonly (but not exclusively) of the US Republican variety. The classic sort of “How to do it” (HTDI) solution is the completely generic “I’d get the both sides into the room and tell them, c’mon guys, let’s roll up our sleeves and just get it done. We’re not leaving here until we’ve come up with a solution.” (That’s for a conflict; if it’s a technical challenge, like cancer, or drought, replace “both sides” with “all the experts”. Depending on the politician’s demeanor and gender this may also include “knocking heads together”.) The point is, they see solving complicated problems the way they might appear in a montage in a Hollywood film: Lots of furrowed brows, sleeves being rolled up, maybe a fist pounds on a table. It’s a manager’s perspective. Not a very intelligent manager. Of course, it sounds ridiculous to anyone who has ever been involved in the details solving real problems, whether political, technical, or scientific, but it sounds good to other people who have only seen the same films that the politician has seen. Continue reading “How to rid the world of genocide”

“Serving the purposes of the Israeli apartheid and colonial regime”

The American Jewish reggae singer Matisyahu has been expelled from a Spanish music festival, for refusing to issue a statement in support of a Palestinian state. Apparently such loyalty oaths are required of suspect persons, such as Jews. His silence, they said, serves “the purposes of the Israeli colonial and apartheid regime”.

This buttresses the view that BDS has a significant dollop of antisemitism in its ideological matrix, even if not every BDS supporter is antisemitic (and not everyone motivated partly by antisemitism is entirely or even consciously motivated by antisemitism).

This takes me back to 2007, when one UK academic union, the National Association of Teachers in Further and Higher Education (since melded into the University and Colleges Union (UCU)) couldn’t find any more relevant challenge to higher education in the UK than a boycott of Israeli academics who do not “publicly dissociate themselves” from Israeli “apartheid policies”.

I immediately recognised a problem: What is the appropriate form for expressing such dissociation? And how would we test whether the self-criticism was sincere, or merely careerist dissimulation. After all, we wouldn’t want crypto-Zionists sneaking in to British universities and scientific conferences, infecting them with the taint of racism and colonialism. Leaping into the breach, I composed a form to enable the aspiring good Israeli to have his anti-Zionist bona fides tested and confirmed by the proper authorities.

“I wish that I was a film comedian”

I’ve just been reading David C. Cassidy’s updated version of his Heisenberg biography, titled Beyond Uncertainty. He reports that in May 1925 Wolfgang Pauli, who was struggling together with Heisenberg to apply the new quantum theory to calculate the spectral lines of hydrogen, wrote in a letter

Physics is at the moment once again very wrong. For me, in any case, it is much too difficult, and I wish that I was a film comedian or something similar and had never heard of physics.

Here is a challenge for a young postmodernist film-maker: Produce the silent-film comedies that Wolfgang Pauli would have made, had he never heard of physics (or abandoned physics? Presumably they would have been different…)

Alternatively, a science fiction author could write about a universe governed by Charlie Chaplin’s quantum mechanics.

International queueing theory

Queueing up to board the Eurostar in London recently, I saw these very conspicuous signs engraved in the doors leading to the platforms

On apprend l’art de faire la queue comme les anglais.

Attributed to “Jean-Marc, Paris”. There was also a translation, something like “We are learning the art of queueing up like the English”. Is this intended to shame the French passengers into behaving well in the queue? To flatter the English? To mock them?

Of course, while the English are very proud of their queueing habits, there are greater superlatives imaginable. Historical context is crucial, though. If the French develop their skills further (and if the Germans make more progress in dismantling the European economy), perhaps one day they will be able to say they have learned “the art of queueing up like the Poles (Communist era)”. Or even the Russians. If they get really advanced, they might learn the art of queueing up like Depression-era Americans.

And that’s the pinnacle. Presumably they’ll never have to learn to queue up like these people…